WHAT’S NOT TO LIKE ABOUT IT?

In 2016, Amazon acquired the site of the former Jacob’s factory in Tallaght, South Dublin, to build a data centre. Two years later, they applied to build a second data centre on the same site, next to the first one. This time, however, the local authority South Dublin County Council (SDCC)’s approval was granted on the condition that Amazon would facilitate access to their waste heat to power a local district heating scheme. “Waste heat” is generated by data centres through the process of cooling their processors and electrical equipment.

In 2023, the Tallaght District Heating Scheme (TDHS) was inaugurated in the presence of Minister for the Environment Eamon Ryan. The initial infrastructure, comprising the energy centre and some first connections, was built at a cost of €8 million, part state and part EU funded. The project was jointly developed by SDCC, Codema and Finnish energy company Fortum. The scheme itself is run by Heatworks, Ireland’s first not-for-profit energy utility fully owned by SDCC.

In receipt of multiple awards, the TDHS has been unanimously branded a success from both an environmental and social perspective. First, the scheme is said to have helped save a total of 1,100 tCO2 in the first year of its operation. Second, it is the first Irish not-for-profit energy utility, aiming to provide all connected buildings with affordable energy. What is more, in addition to its connection to local government and university buildings, it will power a forthcoming affordable housing scheme comprised of 133 cost-rental apartments. So, what’s not to like about it?

CLIMATE MITIGATION BENEFIT?

One of the claimed successes of the TDHS is its emission saving based on the use of waste heat by connected buildings instead of other energy sources. A focus on the TDHS emission saving, however, makes us overlook on which terms the scheme came to be implemented in the first place. Indeed, the TDHS was not built to offset the existing emissions of an existing data centre but only imposed as a condition for the construction of a new data centre! In other words, the real energy cost of the TDHS is the energy use and associated emissions of a whole new Amazon data centre! As observed by Hannah Daly, mitigation remains meaningless as long as it is accompanied by uncontrolled expansion. Ireland’s renewable energy generation is a case in point: how can it be expected to cater for ever-growing consumption while it cannot even cope with existing needs? Between 2020 and 2023, it only met 16% of the new electricity demand from data centres.

In contrast, in their district heating roadmap for South Dublin, Codema argue that (waste) heat sources should be considered separately from the actual (industrial) processes that originate them: these heat sources are a “by-product of a separate primary process”. From their perspective, the Amazon data centre waste heat is described as a “local”, “indigenous” energy source and the district heating it powers a “lower or zero carbon emissions” technology. Such a view, however, clearly obfuscates the highly contested energy supply chain which the waste heat is part of. In addition to its electricity consumption (21% in 2023) and carbon emissions (1,530,000tCO2 in 2023), the data centre industry puts communities across Ireland and beyond under increased pressure to bear the brunt of unsustainable energy infrastructure developments. In North Kerry, communities are faced with a plan by Shannon LNG to build a liquefied natural gas facility on the Shannon Estuary that would import fracked gas from the US. As for wind farms, they are too often erected on peatland, which may have devastating environmental effects as seen in Donegal in 2020. In this particular case, the wind farm developer had entered into an exclusive purchase agreement with Amazon.

ENERGY POVERTY BENEFIT?

In addition to its climate mitigation benefit, the TDHS is claimed to have the potential to address energy poverty. It implies that the ‘cheap’ energy obtained through the TDHS would benefit the most socially and economically marginalized residents of Tallaght. As of March 2025, the only confirmed residential connection to the TDHS was the forthcoming 133 cost-rental apartment complex being built by the local authority on public land in the centre of Tallaght. Allegedly, by providing 133 lower-middle-income households with affordable energy, the project could be seen as positively impacting energy poverty. The scope of the affordable housing scheme, however, must be assessed in context.

To begin with, the 133 cost-rental apartment scheme was not the only initially planned TDHS residential connection. In fact, for a number of years, those managing the TDHS project were relying on the expectation that a nearby private land plot would be redeveloped and connected to the district heating in its first development phase. The now abandoned large scale build-to-rent project was to include 1423 apartment units and 339 student units. The planned private development, already enormous in scale, was only one of many being discussed and planned in immediate proximity to the district heating infrastructure. In the current housing policy context, newly-built private rental apartments would only be accessible to higher-middle-income residents and therefore unlikely to include residents most vulnerable to energy poverty. What is more, nothing would prevent private landlords to capitalize on the green, affordable energy supply through increased rent and therefore cancel any benefit drawn from energy affordability. From such a scaled perspective, the energy poverty benefit of the 133 cost-rental apartments becomes far less significant.

Even more concerning, cost-rental apartments are aimed at the higher end of low-income households, explicitly excluding public/social housing and HAP tenants. But looking at Tallaght where the TDHS is being developed, what is the situation there? Tallaght and its surroundings host a high concentration of disadvantaged to very disadvantaged areas with a high proportion of public housing tenants: 17% overall and in some cases close to 80% in the most disadvantaged areas. In other words, it means that by design the cost-rental apartments cannot address the energy needs of the most socially and economically marginalized in its surroundings, no matter how many cost-rental apartments are built and connected to the TDHS. Furthermore, while cost-rental apartments are not accessible to public housing tenants, massive disinvestment in public housing in the last decades means that these tenants are too often left to live in decaying housing infrastructure that further compounds energy deprivation. The 2022 CSO data show that 73.3% of all local authority homes in Ireland have a BER rating of C, D or E.

Ironically, fieldwork conducted in 2022 revealed that, in a small public housing estate located only 250 meters from the TDHS energy centre, residents from the Traveller Community are left to face the worst energy access conditions. One of them, who lives in a caravan in wait of social housing, explains that their small gas heater must be left on at all times – “you have to leave it on because it’s so cold, you know” – and refilled every two weeks for €50. “It’s so cold, like, this is, this is gone up now 45, 55 a bottle, you know what I’m saying, this is very hard for me”. Another resident, this time living in one of the houses of the estate, makes the following statement: “It’s freezing, it’s freezing in this house and I am very, very cold in it”. Meanwhile, in Tallaght’s city centre, rough sleepers can be seen sheltering against the rain under the porches of public buildings connected to the TDHS.

A “PUBLICLY OWNED” ENERGY UTILITY ?

Heatworks, the company running the TDHS, is said to be “publicly owned”, but how does this claimed public ownership work in practice? Let’s look at three aspects of it: decision-making, access to information, and land ownership.

In terms of decision-making, the TDHS was subject to a Part 8 planning approval process. The process consists of the collection of public observations which are summarized in a report before being discussed by council staff and local elected representatives during a council meeting. As explained in the Codema district heating roadmap, the report “outlines whether or not it is proposed to proceed as originally planned or to proceed with a modified proposal”, which is another way to say that Part 8 projects may be altered but not refused. A resident who attended a local authority TDHS public meeting observed: “There was a public meeting once, but it was fait accompli, you know”. Even more telling are the district heating public engagement guidelines given by Codema to local authorities. They are very explicit about the necessity for local authorities to prioritize stakeholder engagement and they are very specific about how such prioritization should occur: “One way of prioritising stakeholders is to rank each one on the level of influence they could have on the project and also on the level of interest and enthusiasm they display for being involved”. Publicness sounds a lot more like exclusiveness here!

Obviously, access to decision-making is only meaningful if it is based on proper access to information. However, during the doctoral research at the origin of the present piece, access to information was found to be extremely poor. Three public officials involved in the TDHS project were contacted for interview but kept delaying it until they finally sent in a colleague in their place who had little idea about the TDHS. The manager of the site hosting the two Amazon data centres was sent an interview request by registered post but did not respond to it. Following such poor staff access, freedom of information requests were submitted but anything that was obtained through them came in heavily redacted. While piles of technical-jargon-oriented documents were produced, some of them publicly accessible, no clear, lay summary of the benefits versus downsides of the project for both local communities and Amazon was found. Amazon is only ever presented as a generous, disinterested benefactor making their waste heat and land available for free. But what about the water cooling produced through the heat exchange which benefits Amazon once the cooled water is returned to them? Why are they not charged for the cooling process as assumed by the company who peer-reviewed the TDHS business plan?

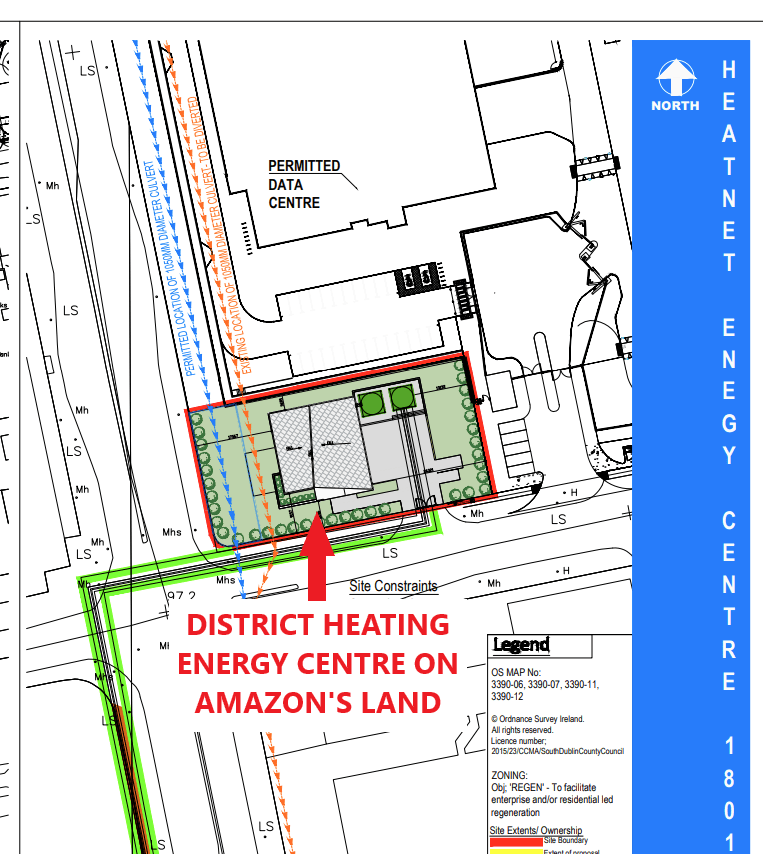

The ‘free Amazon land access’ leads us to the third point challenging the publicness of the TDHS. The district heating energy centre, the main infrastructure of the project housing the equipment to convert, store and distribute heat to the area, is actually located on Amazon’s land, beside their second data centre. In 2023, a freedom of information request was sent to SDCC to ask for a copy of the lease agreement. Surprisingly, on 17 August 2023, the council response was that, to date, the agreement hadn’t been finalized: “We anticipate the completion of this document in the coming weeks and if you wish to make contact in 2-3 months we can advise whether a redacted version of the executed document may be available, subject to third party approval.” This is highly surprising given that the district heating energy centre had been inaugurated a few months earlier in April 2023. In other words, it means that the publicly funded infrastructure was erected on private land without a finalized agreement. In February 2025, another freedom of information request was sent to obtain access to the finalized lease agreement, but access was refused: “This legal agreement is not publicly available as it contains information whose disclosure could prejudice the conduct or outcome of contractual or other negotiations of the person to whom the information relates.” In short, our “publicly owned” district heating infrastructure is on Amazon land and we have no means of accessing the terms of the lease. What would happen to it if the property is transferred to another owner?

NOT MENTIONED: THE JACOB’S SOCIAL CLUB

While much publicity is made of the benefits of the TDHS, the fact that the district heating energy centre was built on the demolished Jacob’s social club is barely if ever mentioned. The idea of building the social club on an unused plot of the Jacob factory’s site was first initiated by the factory’s employees in 1980. The employees would own the bricks and mortar and pay rent to Jacob’s for the land. “Life Members” invested in a brick each to cover the initial construction cost and thereafter were joined by other members for a small annual fee. Initially reserved for Jacob’s employees, the club subsequently opened to other local residents through word-of-mouth. Maintenance was funded through membership fee and drinks money, and energy bills were paid by Jacob’s. When the Jacob’s factory closed down in 2009, subsequent landowners maintained access to the social club and continued to pay the energy bills.

However, when Amazon acquired the site in 2015, the Club chairperson explains how things went very differently: “The Monday following the story in The Echo about Amazon taking over, I went to the club and found that the electricity and water was cut off. We can’t get a hold of anyone in Amazon. (…) The club is just getting left behind and bullied out of the building.” At the time of the takeover by Amazon, the social club was still very much in use: “Up to 50 old age pensioners used the site on a weekly basis and took part in art classes every Thursday, played pool on Sunday and met up for social nights every second Tuesday and Thursday.”

Once Amazon had closed the gates, no one was allowed in again: “we weren’t allowed back into it. Like the gate was locked, they, we originally had a lock on it, and they took the lock off and they changed the lock” (former Jacob’s employee). It means that no memory of the Club could be saved: “There was a mirror in the social club, they had a, what did they call it, a stage, now it was a very small stage, where the band would sit, behind the bands there was actually a mirror up on the wall, which had Jacob’s social club engraved on it and I would have loved if, before the factory or before it had been demolished, (…) we’ve got that (…), but you weren’t able to, they just locked the gates and no one else was able to go back into it.” (former Jacob’s employee)

While the detail of the talks between Amazon and the club members is not fully known, the outcome of the negotiations was widely publicized: Amazon paid the social club members a lump sum of €400,000 and members voted in favour of donating it to children’s charities. Talking to a former Jacob’s employee, however, it was confirmed that the committee had tried to obtain Amazon’s help in relocating the social club but that this aspect of the talks had not been successful. As observed by the former employee: “it did make them look good because it was public knowledge that Amazon donated for the social club rather than giving out money to the members, so it did make them look good”.

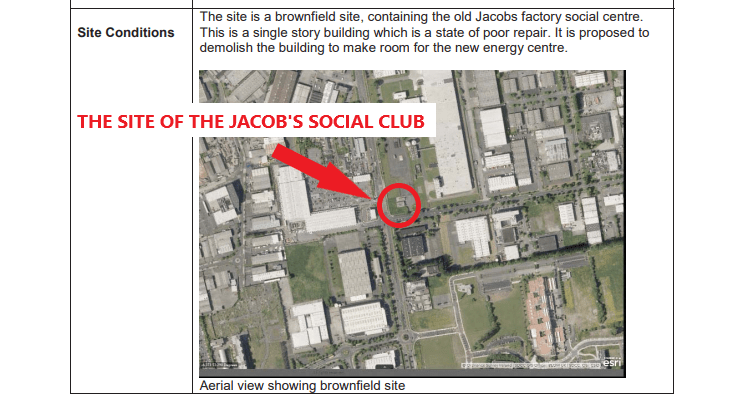

Subsequently, the social club was kept vacant and unused for another three years until its demolition in March 2019. The permission for its demolition was granted as part of the second Amazon data centre planning permission which was to power the district heating energy centre. In fact, the demolition of the social club was to make room for the new district heating energy centre itself. In 2019, SDCC applied to build the energy centre on the site of the demolished social club. This is how things are described in their Part 8 planning application: the site of the social club is called a “brownfield site” and the social club itself is depicted as “out of use” and in “a state of poor repair”. The only photograph of the social club in the report is an aerial one, further diminishing its significance and existence.

The commoning practices which had sustained the social club over the last decades, peacefully coexisting with different private owners prior to Amazon’s acquisition, were brutally severed. Through the demolition of the club, a whole working-class way of life and significant cultural heritage were erased. As put by a former Jacob’s employee talking about their late father, “My father’s life was Jacob’s. Pitch and putt, and the social club. (…) That was his life.”

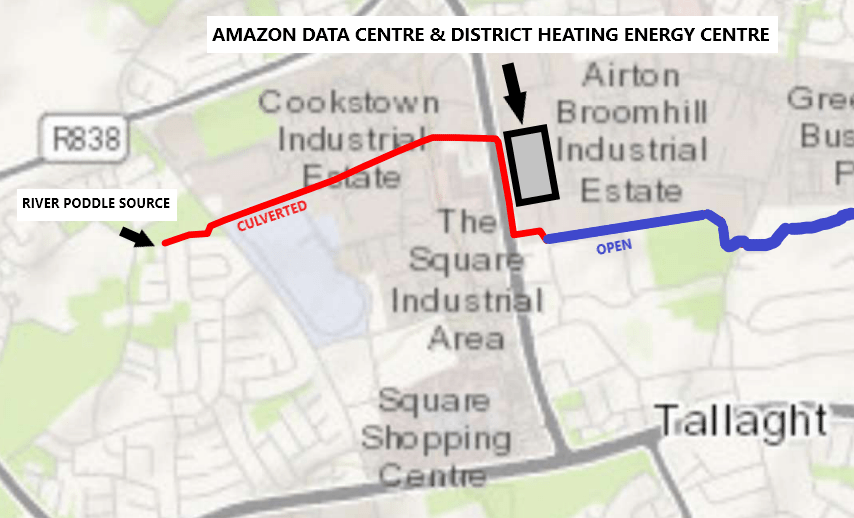

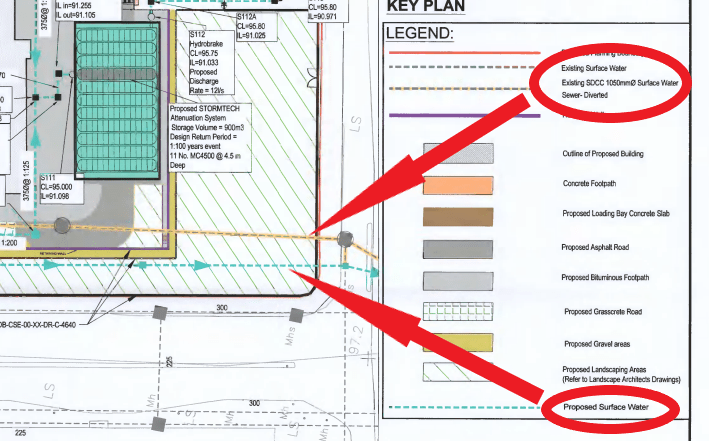

NOT MENTIONED: THE RIVER PODDLE

The Jacob’s social club was not the only thing to be disqualified in the process of developing the TDHS. In the same planning application allowing Amazon to build a second data centre and demolish the social club, they also received permission to divert a piped section of the river Poddle to make room for their second data centre. In the planning application, however, the river is not mentioned by its name but designated as a “1050 mmo surface water drain/sewer”. The dismissing of the river by Amazon’s consultants, fully sanctioned by the local authority, is part of a wider attempt to make the river disappear in this upstream part of the catchment. The practice is no doubt of benefit to the property developers who build on the lands surrounding the district heating facility: indeed, no river equals no need for river-oriented flood risk and environmental assessments. The dismissal of the river at this location is especially at odds with the local area plan commitments to explore its uncovering. And wasn’t the River Poddle one of the first sources of potable water in Dublin and which gave the city its name? Reducing the River to a drain is altogether discarding its ecological and cultural value.

NOT MENTIONED: LIFE ACROSS THE ROAD FROM TWO DATA CENTRES

Also forgotten in the TDHS development process and nowhere to be seen in its success story are the residents living close to the two Amazon data centres. Knocking at a few doors in proximity to the data centres and district heating energy centre in 2022 revealed some of the issues encountered by these residents. Two major issues mentioned during the door-knocking were water access and noise pollution. While water pressure in the area had been very poor for decades, some residents argued that the construction of the two data centres next to their homes made it worse. As one resident put it at the time, “Our toilets won’t fill because of the Amazon, across the road. (…) It’s when Amazon is on, our toilets won’t fill.” Isn’t it incredible that Irish Water worked tirelessly to provide Amazon with all their water needs while residents had been left dealing with poor water infrastructure for decades! As explained by a local tenant, low water pressure means that their washing machine sometimes stops halfway through its cycle and that they have to add water to it manually from a nearby water tank to restart it. Another issue mentioned during door knocking was that of noise coming from the data centres. “You have noise in your house, you know, they can’t open the window either. In the summer you have to leave your windows to keep the sound out, you know, you understand, and they say it’s alright, it’s wonderful.”

WHAT’S TO LIKE ABOUT IT?

This short piece shows that any energy transition success story should be assessed with much caution. Centrally and above all, we must ask: who is telling the story? In the case of the TDHS, most of its success accounts come from public representatives as well as from journalists who most likely have never set foot in the communities bearing the brunt of our data centre driven energy transition. And if they did, have they meaningfully engaged with those communities? Data presented in the piece only offer a short glimpse into the type of classist, racist, gendered inequalities ignored and reinforced through the TDHS. However, they already bring ample evidence that everything that has been done to complete the TDHS goes against the most basic principles of a just energy transition: equity and inclusiveness. Thus, we must ask, what’s to like about it?

Laure de Tymowski (01/11/2025)

Acknowledgments: Huge thanks to All who have contributed to the doctoral research at the origin of the present piece and to All who have helped improve the piece content before publication. Huge thanks also to those helping with the organization of the forthcoming public gathering on 23 November 2025. See you there!

Part of the data presented in this post were quoted in Gerry McGovern’s piece: https://www.hotpress.com/opinion/ai-data-centres-will-eat-you-alive-23123736